The participatory design (PD) approaches aim to elicit individuals’ tacit knowledge and facilitate its expression, informing researchers and promoting more human-centered designs that are aware of diversity. Moreover, they are ways to encourage end-users to feel more actively involved in co-creating tools that they will be the target of. This contributes to personal autonomy, often diminished due to the introduction of assistive robots, and partially addresses one of the most challenging ethical dilemmas in this field: the loss of skills and passivity of users. By leveraging these methods, robotics can incorporate the authentic individual or group preferences that emerge from PD experiments into the aesthetics and functions of machines, promoting comfort and inclusion while avoiding generalizations and biases of experimenters. Additionally, proposing participatory design can be a way to better understand psychological and social dynamics. In this article, besides describing this approach in more detail, I’ll provide a practical example of how we at Scuola di Robotica have included it in our research within the Automatism project, starting with the analysis of some sketches made by primary school children.

Participatory Design Methods

What are the most commonly used tools in this methodology?

Concept Maps: These are a series of predefined cards created by experimenters that can contain sketches, descriptions, words, photos, and provocative “what if” scenarios. They are presented to participants to facilitate focus and brainstorming. Individuals can freely interact with the cards, including drawing or providing verbal or written narratives about the contexts they envision.

Collage and Sorting: Participants may be asked to put together a series of visual elements, expressing categories and concepts defined by the experimenter, through collage or hierarchical sorting.

Storyboard: Narration can be assisted or unassisted, and it can be in an iconic or non-iconic form. Participants may be asked to fill a series of boxes with their drawings to create a story, either entirely freely or with some initial scenario provided by the experimenters. Alternatively, participants may be asked to keep a diary or produce (or find) photographs or videos.

Storytelling: Participatory Design may require the production of a narrative, from which the experimenter can extract categories and subcategories using sociological techniques, which can then be compared with those from other narratives.

Sketching: In some cases, participants may be asked to sketch the robot’s form from scratch, while in others, the researcher may provide the drawing, and the participant defines the functions.

3D Mock-up: Clay, digital modeling, or LEGO can be used.

Interviews and Focus Groups: These can be semi-structured interviews, while focus groups are discussions where the subject is at the center of the design research. They are used to discover attitudes and fears.

Role Play: Participants may be asked to play the role of the robot or the user.

These participatory design methods help ensure that the design process takes into account the perspectives and needs of the end-users, promoting a more user-friendly and ethical approach to robotics development.

Automatism: What We Observed and How We Used Participatory Design

At Scuola di Robotica, as part of the Automatism project [5], an Erasmus+ initiative dedicated to creating educational materials for inclusive use of humanoid robotics in schools, we conducted a series of experiments to assess motivation, engagement, and classroom interaction during activities with Nao the robot.

To understand the children’s attitudes, we proposed various forms of participatory design to primary and lower secondary school classes. The first involved asking them to draw a robot and provide details such as its name, the manufacturer, material, fundamental characteristics, and its function (Robot Identity Card). The second form of participatory design required assisted sketching and storytelling: children were presented with different starting scenarios (school, beach, hospital, and home) and asked to draw a robot, give the scenario a title, and complete it with a brief description (Robot Scenarios).

In addition to these proposals, children were, at times before and at times after, taken to a separate classroom from where they were drawing and examined during activities with the Nao robot. Observers noted instances of laughter, frustration, distraction, interactions among students or with the experimenter related to the activities and robotics, as well as individual focus on the task with Nao and during participatory design sessions.

At the end of the activities with the humanoid robot, students also responded to the Godspeed test to measure animism, likability, anthropomorphism, allowing us to correlate this data with systematic observations and qualitative data.

The children’s drawings will be analyzed using established sociological methods. For now, I’ll share some interesting observations that stood out.

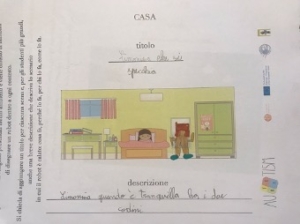

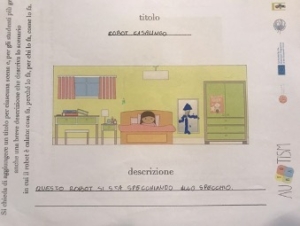

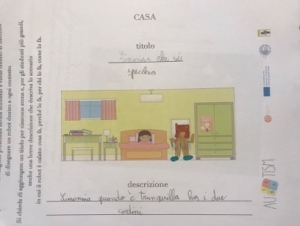

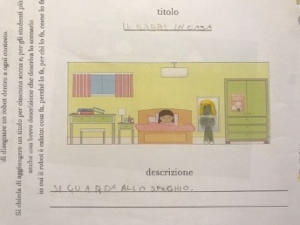

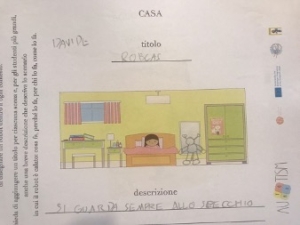

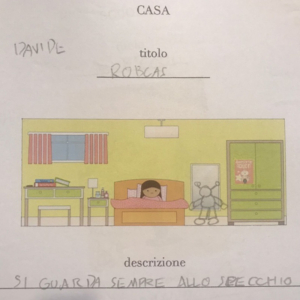

The Mirror

While reviewing the scenarios proposed by the third-grade class in primary school, one curious observation immediately caught my attention. In 4 out of 30 drawings, the children depicted the robot in a bedroom, engaged in looking at itself in the mirror. As you can see, the default scene included a child in bed, a desk, a wardrobe, and a mirror. Many children chose to emphasize the detail of the mirror, placing a humanoid robot in front of it and describing the scene of self-reflection.

The mirror holds great significance in philosophy and psychology. Our face would be the most unknown to us if it weren’t for the mirror. Often, it is used as a metaphor for self-reflection and self-awareness, which is why choosing to place a machine in a similar context is intriguing. A robot that looks at itself in the mirror does so to get to know itself, revealing animistic characteristics in the child.

The participants examined belong to the stage that Piaget defined as the concrete operational stage, when a child begins to move beyond egocentrism and to consider the perspective of others, although still with some difficulty. Therefore, it is not surprising that in many of the drawings examined, the role of the robot is that of an alter-ego onto which they project their own selves. The concrete operational phase can still reveal preoperational childish animism, which precisely involves egocentrism and anthropomorphizing every aspect of the world, not yet being able to distinguish their own point of view from that of others, including that of inanimate entities.

The mirror is a technology capable of fostering self-awareness, influencing self-esteem, and promoting body acceptance. It’s not coincidental that it is used in psychotherapy as a technique to address body dysmorphic disorder and to develop empathy. When a person sits in front of a mirror, they can imagine seeing themselves reflected in the eyes of others, thus stimulating emotional understanding and awareness of others’ emotions. So, yes, there is infantile egocentrism, but in its later stages when there are initial attempts to see things from another’s perspective, albeit with limitations.

Additionally, the robot assumes a role similar to that of a puppet, a transitional object onto which the child projects fears and experiences, separating them. In many ways, it acts as a Jungian Shadow. It’s not coincidental that the mirror serves a similar purpose. Observing one’s reflection means coming to terms with one’s alter ego and its disturbing aspects, thus also becoming aware of them.

The robot necessarily takes center stage in the drawn scene, and the child wants to be at the center as well. Therefore, it’s not abnormal for them to want to recognize themselves and make the robot engage in activities that they themselves would normally do or wish to do. In this case, it’s a way to take advantage of the fiction of drawing, play, and the robot to behave as a rebel; but we will discuss this further in another article…

Conclusion

From this, it becomes clear why noticing this recurrence in children’s drawings is exceedingly interesting. The robot is alive, can become self-aware; it is an alter ego, and the child empathizes with the machine. Robots, then, represent the shadow, the double. When they scare us, they suggest that these fears are terrors towards what we do not accept in ourselves and thus project onto others, including objects.